The productivity penalty of failing to deliver sustainable cooling

As global temperatures rise, it has become clear that a dramatic expansion of air conditioning and the associated energy demand could have serious environmental consequences, and a lack of access to cooling, particularly for those working outdoors, poses a significant challenge for economic development.

Between 1960 and 1991, Singapore experienced rapid economic growth, with an average annual GDP growth rate of 8.25 percent. [1] Its Prime Minister during much of this time, Lee Kuan Yew, credited cooling and the advent of air conditioning as crucial for this growth “by making development possible in the tropics.” [2] During this time, Singapore led by example by installing air conditioning in public buildings, jump-starting the sector’s productivity.

In 2019 the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated that by 2030 the global economy would suffer lost productivity worth USD 2.4 trillion annually due to heat stress, the equivalent of 80 million full-time jobs. [3] Another recent study estimated that the world may already be experiencing an annual productivity loss of 1.96 percent of global GDP due to increased heat exposure. [4]

In the aggregate, these are alarming figures. But they also belie the disproportionate impact on developing economies experiencing increasing heat stress, and the long-term impact heat stress will have on economic growth. It will be these countries, and the sectors that support their growth, that face the most significant productivity penalty due to a lack of access to sustainable cooling.

The global productivity challenge

A 2019 study (Chavaillaz et al.) assessed how exposure to heat affects labour productivity according to different scenarios of climate warming: Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5, where emissions peak in 2040, and RCP 8.5, a worst-case scenario for climate change. [5] The study found that the impact on labour productivity, in terms of GDP loss across the agriculture, mining and quarrying, manufacturing, and construction sectors would disproportionately affect low- and low-middle income countries.

Estimated annual labour productivity loss due to increase in heat exposure in vulnerable sectors, classified by income group (Chavaillaz et. al)

|

Income classification |

GDP per capita* [USD] |

2040 emission peak scenario RCP4.5 [% GDP] |

Worst-case climate scenario RCP8.5 [% GDP] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Global |

|

2.96 |

3.61 |

|

Low |

<995 |

4.37 |

5.91 |

|

Low-middle |

996–3,895 |

5.06 |

5.65 |

|

High-middle |

3,896–12,055 |

1.96 |

2.24 |

|

High |

>12,056 |

0.47 |

0.66 |

Assuming a current climate change trajectory aligned with the RCP 4.5 scenario, this allows for an initial quantification of net economic losses in those vulnerable sectors across the 54 high-impact countries for access to cooling. Across these countries, the estimated annual economic loss due to heat stress is currently USD 630 billion, including USD 517.5 billion in the critical nine countries. In GDP per capita terms, 23 high-impact countries already exhibit losses over USD 100.

23 Countries with per capita GDP productivity losses due to heat stress over USD 100

Per capita GDP losses will be felt across entire economies, but job losses will affect vulnerable groups most intensely. Of the 80 million job losses due to productivity declines associated with heat stress by 2030, 73.7 million jobs will be lost in countries considered to be high impact for access to cooling. India alone accounts for 34 million job losses, and together, the critical nine countries account for 57.6 million job losses. Of the top 10 countries for expected job losses, eight gain over 40 percent of their GDP from labour income.

Estimated number of full-time jobs that will be lost due to productivity declines associated with heat stress by 2030 in 54 countries considered high impact for access to cooling

Projected top ten countries for jobs lost to heat stress by 2030 and associated GDP loss

|

Country |

Estimated number of full-time jobs lost due to heat stress (2030) |

Labour income as a share of GDP (2017) (%) |

Estimated annual GDP lost due to effect of heat stress on labour productivity (2030) (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

India |

34056000 |

49.2 |

$ 134,256 |

|

China |

5479000 |

51.5 |

$ 238,012 |

|

Pakistan |

4603000 |

42.7 |

$ 14,605 |

|

Indonesia |

4018000 |

38.6 |

$ 51,253 |

|

Bangladesh |

3833000 |

42.4 |

$ 13,032 |

|

Nigeria |

3639000 |

67.0 |

$ 19,014 |

|

Vietnam |

3062000 |

40.3 |

$ 11,436 |

|

Thailand |

2637000 |

47.7 |

$ 8,901 |

|

Philippines |

1217000 |

27.0 |

$ 15,831 |

|

Ghana |

1038000 |

49.7 |

$ 2,956 |

Productivity losses in the agricultural sector

The agricultural sector warrants close attention due to the relative size of the sector in low- and lower middle-income countries, and its role in ensuring the sustenance and incomes of poor, rural communities. Of the 54 high-impact countries for access to cooling, 36 have agricultural sectors where productivity losses due to heat already account for more than 1.5 percent of GDP annually. Working hour losses are projected to increase over time in each country, with varying impacts on agricultural labour productivity. Across the countries, the estimated annual economic loss in the agriculture sector resulting from productivity losses associated with heat stress is currently USD 301 billion.

The productivity penalty in the agricultural sector. Note: Countries in bold connote least-developed country (LDC) status.

|

Country |

Working hours lost to heat stress in 1995 (agriculture) (%) |

Income share of agriculture as a ahare of GDP (%) (2017) |

Estimated proportion of annual GDP lost in the agricultural sector due to heat stress under RCP 4.5 |

Estimated annual agricultural labour productivity losses due to increase in heat stress (USD per capita) |

Estimated working hours lost to heat stress in 2030 (agriculture) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nigeria |

5.40 |

66.5 |

3.36% |

$ 66.24 |

9.79 |

|

Bolivia |

0.88 |

54.4 |

2.75% |

$ 92.24 |

1.97 |

|

Congo, DR |

1.58 |

53.2 |

2.69% |

$ 45.83 |

4.15 |

|

Guinea |

2.17 |

58.1 |

2.54% |

$ 21.72 |

4.44 |

|

Laos |

3.18 |

49.7 |

2.51% |

$ 60.96 |

5.71 |

|

India |

5.87 |

49.0 |

2.48% |

$ 49.12 |

9.04 |

|

Chad |

4.87 |

55.6 |

2.43% |

$ 16.14 |

8.80 |

|

Ghana |

6.54 |

47.8 |

2.42% |

$ 49.00 |

11.69 |

|

Timor-Leste |

0.16 |

46.8 |

2.37% |

$ 30.66 |

0.70 |

|

Myanmar |

5.21 |

44.4 |

2.25% |

$ 28.08 |

8.71 |

|

Mali |

4.24 |

50.9 |

2.22% |

$ 18.43 |

7.45 |

|

Morocco |

0.13 |

43.5 |

2.20% |

$ 66.83 |

0.39 |

|

Mauritania |

4.09 |

43.3 |

2.19% |

$ 25.10 |

7.26 |

|

Mozambique |

1.32 |

49.7 |

2.17% |

$ 10.02 |

2.52 |

|

Bangladesh |

6.28 |

42.2 |

2.14% |

$ 33.40 |

9.58 |

|

Pakistan |

6.19 |

42.2 |

2.14% |

$ 31.28 |

8.83 |

|

Burkina Faso |

4.62 |

48.5 |

2.12% |

$ 13.62 |

8.50 |

|

Djibouti |

3.17 |

40.8 |

2.06% |

$ 60.50 |

6.48 |

|

Vietnam |

5.71 |

40.5 |

2.05% |

$ 48.48 |

9.71 |

|

Benin |

7.21 |

46.6 |

2.04% |

$ 23.15 |

12.43 |

|

eSwatini |

0.71 |

39.6 |

2.00% |

$ 79.21 |

1.35 |

|

Indonesia |

4.00 |

38.1 |

1.93% |

$ 73.97 |

7.68 |

|

Cambodia |

9.05 |

37.6 |

1.90% |

$ 26.36 |

14.52 |

|

Yemen |

1.10 |

42.6 |

1.86% |

$ 17.94 |

2.00 |

|

Cameroon |

2.26 |

36.4 |

1.84% |

$ 26.18 |

4.60 |

|

Egypt |

0.35 |

34.9 |

1.77% |

$ 43.10 |

1.05 |

|

Sudan |

6.21 |

34.4 |

1.74% |

$ 52.48 |

10.57 |

|

Gambia |

4.21 |

39.7 |

1.73% |

$ 11.79 |

7.08 |

|

Somalia |

3.62 |

39.6 |

1.73% |

$ 5.35 |

7.42 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

3.17 |

39.4 |

1.72% |

$ 12.68 |

6.20 |

|

Togo |

5.84 |

39.4 |

1.72% |

$ 10.78 |

10.61 |

|

Liberia |

4.29 |

38.9 |

1.70% |

$ 11.88 |

7.79 |

|

Uganda |

0.33 |

38.8 |

1.70% |

$ 10.71 |

1.01 |

|

Senegal |

3.69 |

32.5 |

1.64% |

$ 22.48 |

6.55 |

|

Papua New Guinea |

2.26 |

30.7 |

1.55% |

$ 41.87 |

4.36 |

|

Malawi |

0.26 |

35.1 |

1.53% |

$ 5.47 |

0.51 |

The significance of these losses will be felt differently across economies. The implications of a 2.2 percent GDP loss in Morocco’s agricultural sector, for example, will be less severe than a 2.2 percent loss in Mali, one of many least-developed countries (LDCs) captured in the table. The effects will also be felt more severely by smallholder farmers who rely on production for subsistence. In Sub-Saharan Africa, these farmers make up 70 percent of the population. [6] These estimates do not account for the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic or the locust invasion of 2020. Together, these two shocks are expected to increase malnutrition and poverty, placing more strain on agricultural systems, particularly those in rural areas.

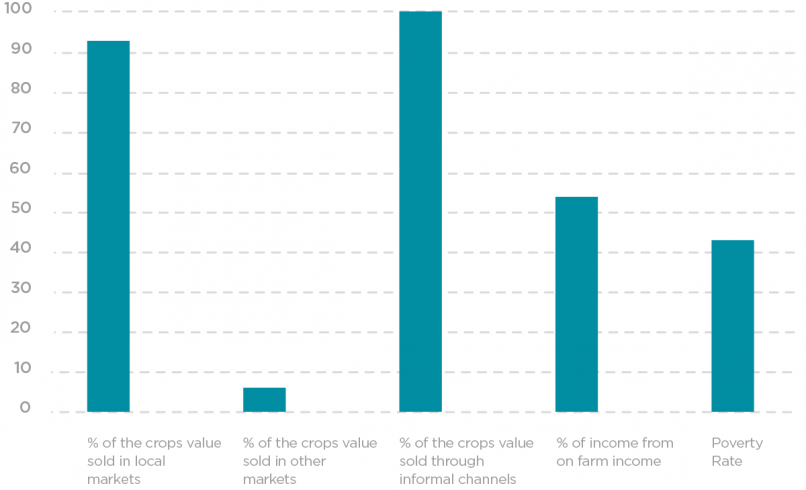

Of the 54 high-impact countries, Nigeria relies most heavily on agriculture, for 66.5 percent of GDP, and experiences the highest productivity losses in the agricultural sector, at 3.36 percent. This is a serious issue in broad economic terms but becomes even more acute at the farm level. Of Nigerian farmers, a full 80 percent are smallholder farmers who generally live in rural areas. [7] According to Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report 2020, only 31 percent of rural Nigerians have access to basic electricity services that would likely be necessary to power electrical cooling solutions. For subsistence farmers, electricity can power refrigeration and support cold chains that could enable them to shift from lower-value crops distributed locally to higher value, more nutritious crops that can be transported to markets further afield. Data from the FAO show how this affects both the markets and the incomes of smallholder farmers in Nigeria, with a strong preference for sale of crops locally and through informal channels. These factors are indicative of a lack of access to cooling that could enable the production of higher-value goods fit for transport to and sale in higher value markets.

Markets and income for smallholder farmers in Nigeria in 2013

The experience in Nigeria is replicated across the African continent, where agriculture employs 60 percent of the total labour force and accounts for 32 percent of GDP. With 70 percent of Sub-Saharan Africans engaged in smallholder farming, the economic environment needs to be conducive to growth. It is also essential for gender equality. Women make up 50 percent of the agricultural labour force in Sub-Saharan Africa but face a wage gap of 15–60 percent compared to men, depending on the country. Land ownership rates among women are also significantly lower than those of men, and where women do own land, they face significant barriers to access finance, agricultural inputs, and information services. [8] The economic productivity of these farmers will also be affected by changes in precipitation, which become more consequential for agricultural yields as exposure to heat stress increases. Even if precipitation remains constant, water stress will increase, particularly in semi-arid regions. [9]

The impact of heat on the well-being of workers

The economic impact of a lack of access to cooling is severe, but so too is the human toll. A recent study on the impacts of heat stress on cardiac mortality for Nepali migrant workers in Qatar revealed a death rate of 150 per 100,000 workers, with the major cause listed as cardiovascular problems. Of 571 deaths associated with cardiovascular diseases among this group between 2009 and 2017, 200 could have been prevented with effective heat protection. [10] These are among the 166,000 documented cases of people dying from heat stress between 1998 and 2017. [11]

The opportunity, therefore, is not simply to avoid productivity losses in terms of GDP, but to increase economic competitiveness, safeguard jobs in crucial sectors, and avoid the unnecessary loss of human life. Singapore demonstrated the economic benefits of increased access to cooling through the second half of the 20th century. Now, as temperatures rise and the effects of heat stress become increasingly apparent, sustainable cooling for all offers developing economies an immediate opportunity to mitigate emissions and build resilient, productive economies.