Chilling Prospects: Addressing heat-related risks in Bangladesh's Ready-made Garment (RMG) Sector

According to Chilling Prospects 2023 analysis, Bangladesh is home to 20.7 million women and 16.5 million men at high risk due to lack of access to cooling services. Women make up as much as 57 percent of the urban poor at high risk in the country as a result of their over-representation in urban slums.

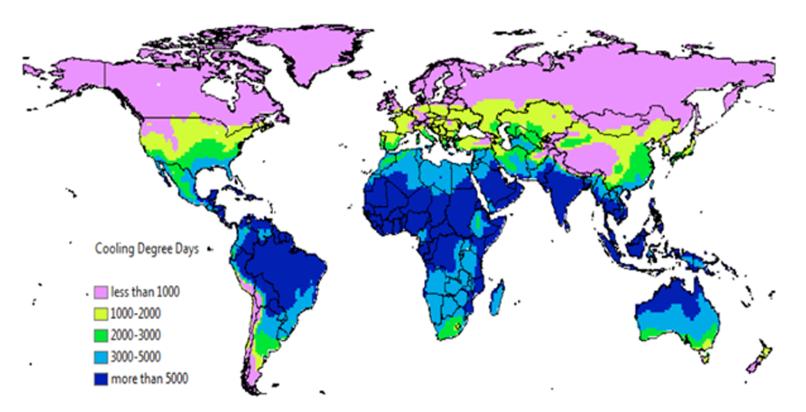

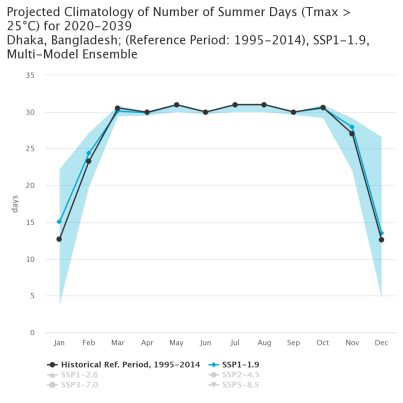

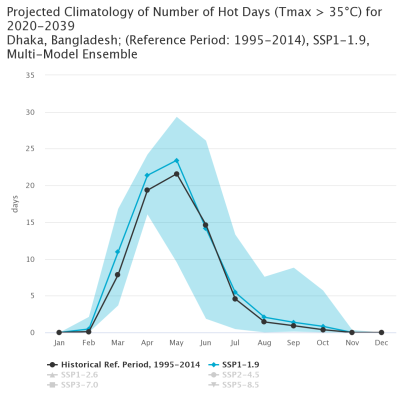

Bangladesh regularly experiences some of the highest maximum temperatures registered in Asia and it is expected to see an increase of up to 3.6°C under a high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions scenario (RCP8.5) by the end of the century. With more severe and frequent heatwaves, it is predicted that Bangladesh will suffer economic losses and occupational health risks in some sectors, particularly in the ready-made garment (RMG) industry. By 2030, Bangladesh is expected to lose 4.84 percent of working hours due to heat stress – the equivalent of 3.833 million full-time jobs.

The RMG industry in Bangladesh is a strong driver of economic growth and female employment. Some of the world's biggest fashion brands operate in Bangladesh, representing around 25 percent of the total garment workforce worldwide, the second-largest clothing manufacturer after China. In 2019, the industry accounted for about 83 percent of the country’s export earnings and represented 12-15 percent of its GDP. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, there are 7,727 establishments in the country, and female workers represent at least 60 percent of the workforce in this industry.