As cities swelter, the ‘playbook’ for sustainable urban cooling is expanding

By: Tilly Lenartowicz and Ben Hartley, SEforALL

With 2023 marked as the hottest year on record and major capital cities experiencing a 52% increase in days reaching 35°C over the past three decades, the negative consequences of extreme heat are a global concern. In less developed and lower-income regions, the situation is dire for 815 million urban dwellers who face more frequent high temperatures without affordable or accessible cooling solutions.

Recently, Delhi, India endured a severe heat wave, with temperatures soaring to above 49°C. Schools were closed in response to the heat, a measure also taken in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and South Sudan, disrupting the education of millions of children. Water scarcity and limited access to electricity in Delhi exacerbate the problem, leaving the poorest unable to cool down with showers or fans. Those with access to fans and air conditioning caused the city's power demand to surge to record highs, straining electricity grids and increasing carbon emissions, further contributing to global warming.

Delhi’s experience underscores the need for sustainably cooling India’s cities. Under the framework of the Cool Coalition, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and RMI, in partnership with the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark under the India-Denmark Green Strategic Partnership, are developing a programme to do just that. Drawing on best practices from around the world, the programme will deliver on-the-ground support to help cities “Beat the Heat.” More details here.

Addressing the broader issues of climate change mitigation and adaptation, poverty alleviation, and energy and water access is crucial to reduce the impact of extreme heat in cities. Reversing or preventing the urban heat island effect—where urban areas are hotter than their rural surroundings due to human activities, dense infrastructure, and reduced vegetation—and increasing adaptive capacity to heatwaves are essential in cities. With holistic and systems thinking, stakeholder collaboration, and solutions targeted at vulnerable populations, city planners and policymakers can achieve equitable and sustainable urban cooling.

Supported by policy and financing mechanisms, the ‘Playbook’ for urban cooling is expanding with highly effective and impactful solutions that can be used by city planners and policymakers.

Heat mitigation strategies

Nature-based urban cooling solutions

Green (vegetation) and blue (waterbody) infrastructure, including street trees, parks, fountains and rivers, lower temperatures in urban areas by up to 6°C compared to more built-up areas. The cooling effect is achieved through evapotranspiration and solar shading.

The 'Green Corridors' in Medellín, Colombia are an excellent example. With 8,800 trees and palms in 30 urban corridors covering 65 hectares, Medellín's urban heat island effect has been reduced by 2°C, with further decreases of 4-5°C expected in the next 28 years.

Passive cooling solutions

Passive cooling strategies, such as cool surfaces and natural ventilation at the city, neighborhood, or building scale, can mitigate the urban heat island effect, reduce overheating and reduce the need for excessive air conditioning use inside buildings. Given that 70% of the buildings expected to exist in Africa by 2040 are yet to be constructed, integrating passive cooling strategies into design and construction norms is crucial and will be hugely impactful.

Where they do not exist, updating building codes and guidelines to include explicit and climate-responsive passive design measures is necessary, along with building the related skills and capacity of engineers, architects, contractors, building inspectors, and other officials.

As an example, cool roofs (using white or high albedo colour roofing materials) can reduce surface temperatures by up to 33°C compared to conventional roofs and decrease indoor temperatures by 1.2°C to 4.7°C. Such temperature reductions can save 18% to 34% of energy for air-conditioning during summer in temperate climates.

Targeting these simple and inexpensive solutions at informal housing developments, typically characterized by poor heat-retaining construction, is crucial for reducing heat exposure among the most vulnerable populations. Initiatives are being rolled out across India, Kenya and South Africa.

Heat adaptive capacity strategies

As Delhi demonstrates, extreme temperatures are already a reality for large populations. Cities must act quickly to provide services that enable residents to adapt and thrive during elevated temperatures and heatwaves. Community-based heat adaptive strategies include not only basic financial and utility services but also:

Cooling Centres

Providing vulnerable populations, including outdoor workers, with access to strategically located cooling centres offers respite from heat exposure. These centres could be air-conditioned public spaces like shopping centres or libraries, or dedicated spaces such as the ‘Net Zero Cooling Station’ for the informal sector in Jodhpur, India.

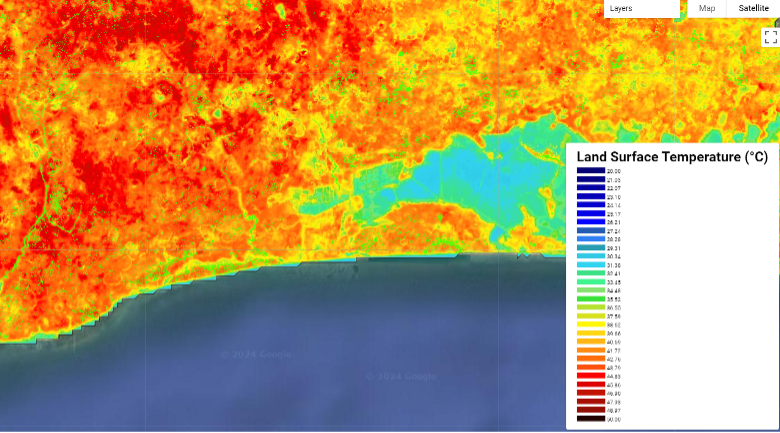

Data-driven geospatial heat risk and vulnerability assessments

Understanding where heat-vulnerable populations live or work and what city characteristics contribute to heat risk can help target solutions and resources effectively. Data-driven heat risk or heat vulnerability geospatial mapping is a valuable tool for planning heat mitigation and adaptation interventions. Such mapping has been widely used in the United States, for example, the Philadelphia Heat Vulnerability Index identifies areas most at risk of heat-related illnesses during hot weather.

A key challenge for such assessments across Africa, Asia and the Middle East and Latin America and the Caribbean is the lack of high-resolution, open-source data. However, more databases and tools are becoming available, such as Charisma’s climate health strategies and adaptation plans for Indian cities. Locally led data collection also fills data gaps while raising awareness among local populations, as demonstrated by a citizen science project mapping heat stress in Johannesburg.

Simulating and projecting the effects of increasing temperatures and urban design interventions can help prioritize resources, informing where street trees, parks, and cool roofs will be most effective. Although more challenging than heat risk assessments that use historic data, standardized methodologies and machine learning can make these assessments more accessible for your community.

Data-driven geospatial heat risk and vulnerability assessments can become the backbone of city heat action plans, supported by tools like the Heat Action Platform from Arsht Rock.

Cooling and heat action governance

A final example for strategies and actions in an Urban Cooling Playbook is the need for clear governance, ownership, and accountability for heat action. Heat issues may sit across planning, health, and infrastructure departments, which requires coordination and oversight to ensure a city's objectives are met. The appointment of a city Chief Heat Officer is a powerful way to address this and has been successful in several cities, including Freetown, Sierra Leone and Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The implementation of an Urban Cooling Playbook will vary from city to city, but with comprehensive planning and collaboration, the expanding Playbook of solutions is making it possible to create more resilient and livable urban environments through equitable and sustainable urban cooling. The Cool Coalition Working Group ‘Urban Heat Adaption’ is supporting cities to take comprehensive action to combat extreme heat, develop guidance and tools, training and advocacy efforts.